The Siena Frescoes of Good and Bad Government

Life gave me the gift of being born in the Tuscany countryside, where I grew up surrounded by the beauty of its landscapes and its enlightenment, as well as the noblest fruits of human work and ingenuity.

These fruits have been handed down from a time when cities in Italy managed to reach a very high standard of living by forming States whose goal was not to attain power but the citizens’ well-being.

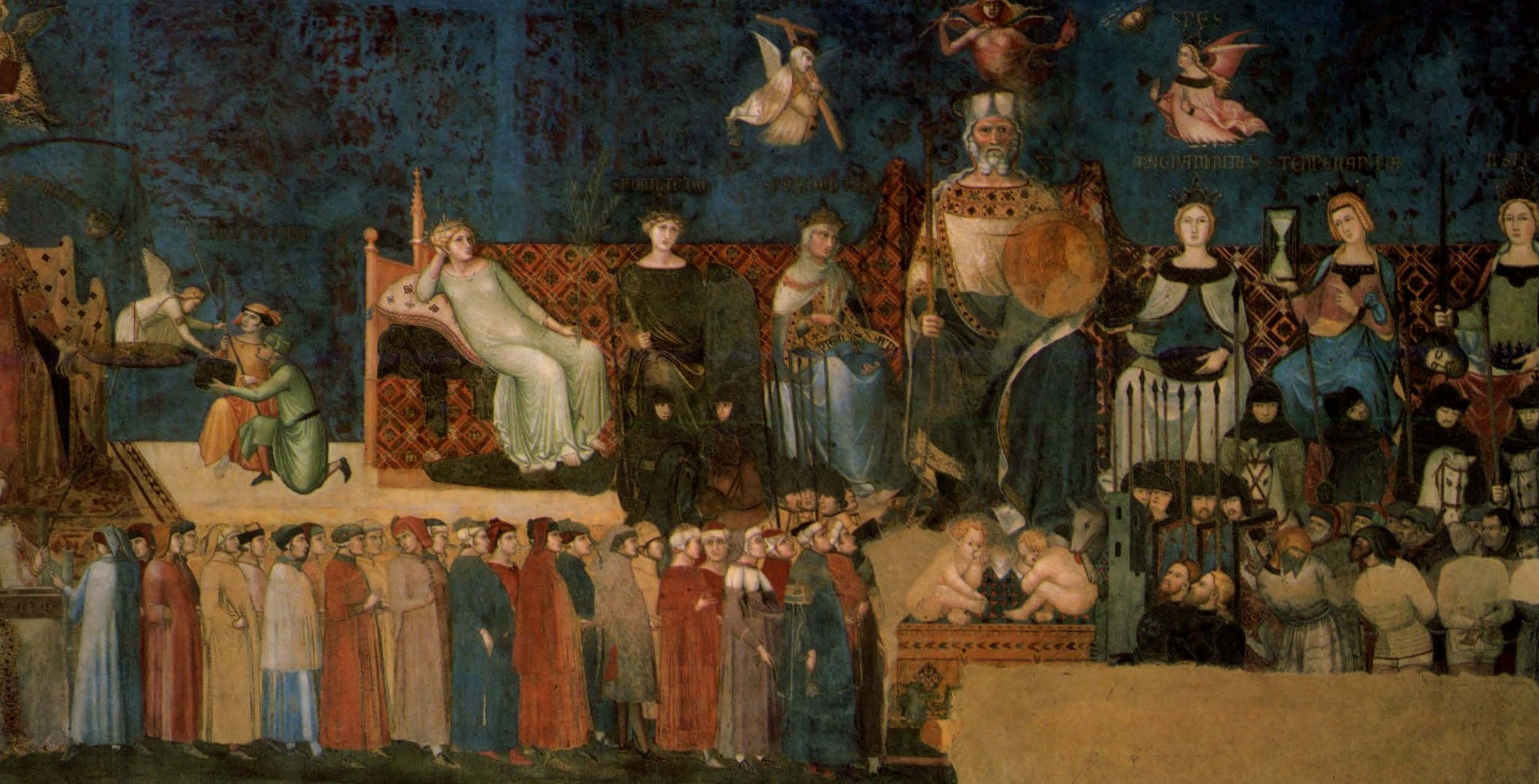

The most eloquent representation of this period are Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s frescoes of Good and Bad Government, which are located in Siena’s “Palazzo Pubblico”.

I still remember the first time we were taken to see these frescoes by our schoolteacher. Today, I enjoy being able to show them to others who are unfamiliar with them.

These frescoes remain highly topical and I believe that their message is still very relevant in today’s world.

This is why I have decided to make them the focus of the first article of my blog.

What was the historical context behind the painting of the frescoes of Good and Bad Government? What was their intended message for the Sienese and for humanity? What has been the impact of their message today?

Ambrogio Lorenzetti was commissioned to paint the allegories of Good and Bad Government by the Council of Nine, which governed Siena from 1287 to 1355, a time when this city was at the height of its power and wealth and was one of the fifteen most important cities in Europe.

Siena owed its power and wealth to the Via Francigena, a system of roadways and paths used by pilgrims coming from France to get to Rome, and which was also a key route in terms of trade between the East and West. Sienese merchants could use this route to export their goods to the north in Europe and import spices, fabrics and precious stones, splendid as well as a result of their colours and artistic style, from the East.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti was instructed to use these frescoes, painted between 1337 and 1339, to sing the praises of the sophisticated political model that was the Commune, the Republic of Siena.

The frescoes are situated in the Hall of Nine, where the (nine) members of government would meet, and cover three walls: the allegory of good government (northern wall), the effects of good government in the city and in the country (eastern side, from where the sun rises!) and the allegory of the effects of bad government (on the opposite side, where the sun goes to die!).

At a conference organised after the European elections last May, I was captivated by a passionate analysis given by Mariella Carlotti, an art historian. She explained the allegory of Good Government in great detail and pointed out the figure of the lady seated on the throne, adorned in purplish-red and gold garments; she represents Iustitia (Justice), punctuated by the phrase: “Love justice, ye that be rulers of this land”. This is the opening sentiment of the Book of Wisdom in the Bible. It is also the phrase that can be read in the scroll that Jesus holds in his hands in the Maestà by Simone Martini, located nearby in the Map Room, where the General Council of Siena, the city’s parliament, would meet. Lastly, it is this phrase that Dante sees appear in the sky of Paradise in the Divine Comedy.

Two other figures are featured at the centre of this painting: Wisdom and Concord, who are linked by a cord to the citizens who hold it out in turn to the Commune of Siena, represented by a person dressed in black and white, the colours of the city.

It is not possible to touch here on all of the allegory’s details and in order to understand them, it would be necessary to include references to philosophical concepts and to the world of Aristotle and Saint Thomas of Aquinas, whose ideas lie at the heart of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Focusing next on the wall to the right, it is easy to become engrossed by the images depicting the effects of Good Government. Ambrogio Lorenzetti portrayed in wonderful detail its characteristics and results. The easy lifestyle and the beauty of the city, which is recognisable as Siena, can be seen alongside signs of economic growth. Everyone is bustling about and at every street corner, people are working; the peasants and city folk exchange products and news. Children are playing. Young girls are dancing, a maiden in red is about to get married and start a new family amidst a setting of happiness and peace.

This ambience is in complete contrast to the allegory represented on the opposite wall which shows war and destruction, the consequences of bad government, in a fresco composed of three parts: the allegory of bad government, its effects in the city and its effects in the country. A cross-eyed figure with horns, representing the tyrant, towers over the allegory of Bad Government. For Lorenzetti and the period in question, a tyrant was not a dictator. A tyrant was someone who only considered their own interests and overlooked the common good.

« Love justice, ye that be rulers of this land .»

What can we learn from these frescoes?

First of all, these frescoes communicate through imagery. In 1310, the government of Siena had the city’s statutes translated into Tuscan so that all of the Sienese could understand the laws and regulations of community life. In 1337, when the commission of these frescoes was given to Ambrogio Lorenzetti, the Government of Nine wanted to tell all of its citizens, even those who could not read, that the best form of governance possible was the republic.

In the centuries that have passed since, history has certainly not given us many examples of governments with such a high-minded view of politics. The Nine who made up the government of the Republic of Siena carried out their duties on a rotational basis over a period of three to six months and remained confined in the City Hall while exercising their official functions in order to give themselves entirely over to their ideals and to remain completely dedicated to their mission.

What was their mission? To promote the Common Good in opposition to private interests. The original title of these frescoes was “the Common Good and Peace” but it was not until the 17th century that people began to refer to them as “Good and Bad Government”.

Today, the frescoes of Good and Bad Government help us to see that respect for such ethical values as justice, wisdom, concord is essential to good government, the entity that ensures the “Common Good”, of benefit to all.

They also show us that this extraordinary mode of governance characteristic of the Italian republics in the Middle Ages, the City-States, was born in the cities where one-third of the citizens genuinely took part in public and political life.

The frescoes also serve as a reminder that these City-States, including the shining example of Siena, had built up their power and wealth through trade and exchange with the rest of the world and that it was these flourishing societies that gave birth to the Renaissance, which contributed to the blossoming of Europe and humanity.

When looking at the frescoes of Good and Bad Government, one is immediately struck by the beauty of the painting itself and the power of its message but, on a personal level, what enthrals me the most about them is the realisation that this civilisation succeeded in encapsulating the most beautiful thing that the world and humanity had achieved up to that time. These images, originating within a city, are universal and can touch the soul of every human being and can speak to the whole planet through the ideas that they communicate. Undoubtedly, this explains why, even though part of me will always remain attached to Tuscany and my identity, I feel at home anywhere in Europe and all over the world.

The following sources were helpful to me in writing this article:

- France culture, the radio broadcast “Concordance des Temps” on “Les Cités Italiennes: laboratoires d’une république” by Jean Noël Jeannenay (on 9 November 2013)

- Patrick Boucheron’s book “Conjurer la peur : Sienne 1338 : essai sur la force politique des images”

- Mariella Carlotti’s conferences which are available on YouTube.

The inspiration for writing this article was given to me by Elisabeth Gateau, former Secretary General of the Council of European Municipalities and Regions (1989-2002) and of the United Cities and Local Governments (2004-2011), in her message to me upon my departure from CEMR. I wish to express my heartfelt appreciation and thanks for her words which greatly touched me.

All news

All news